The Spark

Post 4: How Shadow QE and a looser SLR ignite the bull-market inferno and unleash a crime super-cycle

Executive Summary (TL;DR)

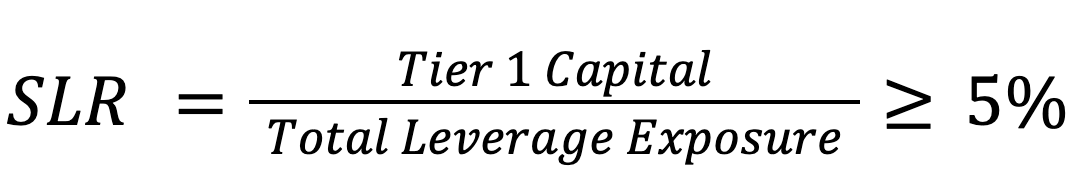

Washington is preparing to ease the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) for big banks—from 5% down to ~3.5–4.25%. That single move frees balance sheet capacity just as pending stablecoin bills would let institutions turn ≤93-day T-bills into spendable digital dollars. The result? A form of shadow QE—privately executed, publicly felt.

Duration risk shifts onto banks. Yields compress. Liquidity floods. Capital pours into both TradFi and crypto. But the same digital rails fueling this bull cycle also accelerate an offshore crime loop, powered by untraceable USDT flows.

As U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently forecast:

“Stable-coin demand will hit $3.7 trillion by the end of the decade.” [source]

That’s not a side bet. It’s the next foundation of dollar liquidity. Once trillions move through digital channels, every plumbing tweak, like the SLR rollback, becomes a structural inflection point.

For deeper context, revisit Post 3: Shadows Beneath the Ice, where we examined the geopolitical strategy behind stablecoins. That once-contrarian thought is now gaining mainstream traction. As Bessent puts it:

“Crypto is not a threat to the dollar. In fact, stablecoins can reinforce dollar supremacy. Digital assets are one of the most important phenomena in the world right now—yet they’ve been ignored by national governments for far too long.” [source]

This Substack maps that hidden river, tracking shadow finance, so you see the cracks and the trades before the headlines hit.

Because once the spark is lit, you don’t just get a rally—you get a bull cycle fueled by shadow liquidity, and a crime super-cycle moving just as fast.

The Prediction: Fire in the System

Eight months ago, Arthur Hayes made a prediction I laughed off:

“Without it, banks won’t absorb large amounts of long-term Treasuries. Suspend the SLR, and they get the capital relief they need to step in. Wide-open balance sheets.”

At the time, it sounded absurd. Congress was gridlocked. The Fed was hawkish. The White House was fiscally cautious.

Debt was piling up like dry timber—but the political weather looked damp, with no spark in sight.

Then, on June 18, Bloomberg broke the news:

"U.S. weighs cutting the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) to 3.5%."[Source]

Suddenly, Hayes didn’t sound crazy.

He had simply seen the fire before the rest of us even started smelling smoke.

Fuel? Stablecoins, synthetic dollars backed by short-term U.S. Treasuries, are already sloshing through markets. They move fast, trade globally, and act like high-velocity digital cash.

Oxygen? The Treasury faces a $9 trillion financing wall and wants to lock in longer-duration funding with 10–30 year bonds. But banks avoid those, because they eat up balance sheet space and hemorrhage value if rates rise… unless the SLR loosens.

Spark? A lower SLR frees banks to buy long bonds for yield while still holding short-term T-bills to issue stablecoins.

One rule change lets banks play both roles: absorb duration and fuel digital dollars.

To understand why this single regulatory move could ignite the next market cycle, we need to dive deep into the financial plumbing beneath the headlines.

II. The Fuel Accelerant: Stablecoins Fill the Pipes

Stablecoins were the fuel already soaking the system’s pipes. But fuel alone isn’t enough to ignite a fire.

As covered in Post 3, stablecoins are no longer fringe. They dominate short-term liquidity, pouring about $260 billion into markets through purchases of 3- to 12-month T-bills, trimming front-end funding rates. Even if U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is right and stablecoin issuance hits $3.7 trillion, that is still just starter fluid. It pales beside the Treasury’s looming refinancing calendar:

$9.2 trillion of notes and bonds mature in 2025 alone

≈ $17 trillion more comes due over the 2025‑2027 window

The U.S. Treasury needs buyers for 10, 20, and 30-year debt, but banks won't touch these long-dated bonds unless the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) loosens. These bonds carry significant duration risk, tying up capital for decades and quickly losing value when interest rates rise.

Fuel has pooled at the front end. But without a spark, the long end remains untouched and dry.

The spark that's still needed?

Regulatory relief.

Lowering the SLR, would give banks room to absorb long-term bonds, finally setting the system alight.

III. The Spark: Why the SLR Sets the Fuel Ablaze

The SLR was created as a backstop, a financial fire code born from the ashes of the 2008 Financial crisis, when banks burned down after trusting even the top-rated, AAA slices of mortgage-backed securities.

In this case, those assets weren’t safe. They were gasoline.

At the time, banks looked secure on paper. These securities were labeled "risk-free." But when confidence cracked, everyone rushed for the exits.

Safety turned deadly, not because each asset was toxic on its own, but because everyone held too many at once.

The danger wasn’t just asset quality; it was concentration and scale of exposure.

That’s the risk the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) was built to contain.

Unlike traditional capital rules, the SLR is blunt and unforgiving:

It treats every asset as potentially flammable, no matter the label.

Even U.S. Treasuries, long seen as the safest asset in the world, count fully toward a bank’s leverage exposure.

In other words, the SLR doesn’t measure credit risk, it measures how much total exposure a bank is carrying.

And in a leveraged system, as explored in Post 2: The Cold Room, even “safe” assets become dangerous at scale.

1. How the SLR Works (and Why It Chokes Duration)

Currently, for the largest U.S. banks, the minimum required ratio is 5%.

Here’s the catch:

Every new Treasury bond adds to the denominator, total exposure, but not to the numerator, capital.

That means even “safe” assets quietly erode a bank’s regulatory buffer.

Drop below 5%, and banks face three unappealing options to remain compliant:

Issue new stock. This lifts Tier 1 capital but dilutes existing shareholders and often dents the share price.

Keep more profits in‑house. Cuts dividends or buy‑backs; helps capital over time but drags on return on equity and disappoints investors.

Shrink the balance sheet. Sell assets or run loans off; today that means crystallizing losses on Treasuries bought when yields were lower.

Because Treasuries devour scarce leverage capacity without helping the numerator/Tier 1 Capital, they can feel toxic under a tight SLR.

But a lower SLR flips the script.

Each dollar of capital can now support more assets.

Banks can warehouse long bonds and still park fresh T‑bills to keep the stable‑coin engine firing on all cylinders. Thus, this SLR rollback may be precisely the regulatory spark to ignite the fuel already pooled beneath the system.

Why ‘Safe’ Treasuries Still Handcuff Banks

Treasuries may be “safe,” but they’re operationally punishing under current rules:

Low-yielding: Barely profitable, especially amid persistent inflation (4-5% yields).

Capital-intensive: Each bond lowers the SLR, tying up precious balance-sheet space.

Illiquid in crises: Difficult to offload quickly without incurring steep losses (as Silicon Valley Bank painfully discovered).

The result?

An incentive trap: Treasuries devour regulatory capital without delivering commensurate returns. Banks shun them not for fear of default, but because the rules make large positions irrational.

As a reminder from Post 1, many big banks today face two compounding problems:

1. Massive unrealised losses. Bonds bought at COVID-era lows are now deep under water in “Held-to-Maturity” buckets, paper losses that become wildfires if sold.

2. Tight SLR limits. Every new Treasury inflates exposure(denominator) but does nothing for Tier 1 capital(numerator).

Bottom line:

Rising yields have already crushed bond values

Balance sheets are stretched

New Treasury purchases worsen leverage ratios and anger shareholders

So why would banks buy more Treasuries now? To answer that, we have to revisit what really drives their business model, and how a lower SLR could flip the incentives.

3. The Pressure Cooker: How SLR Squeezes Bank Profits

Banks earn profits the old-fashioned way: borrow cheaply and lend at higher rates. For example,

They pay you 3% on your high-yield savings account: that’s the cost of borrowing your money.

Then they reinvest that money in higher-yielding assets, like loans or 4.5% Treasuries.

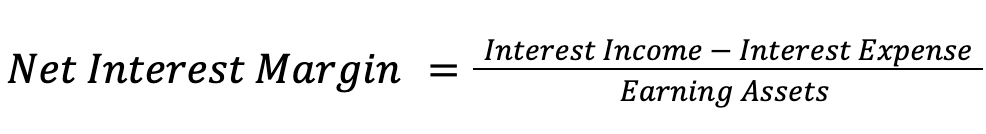

The 1.5% difference is their Net Interest Margin (NIM), the lifeblood of bank profitability.

To formally define it the equation is this:

Treasuries are earning assets → they increase the denominator

They also generate interest → they also increase the numerator

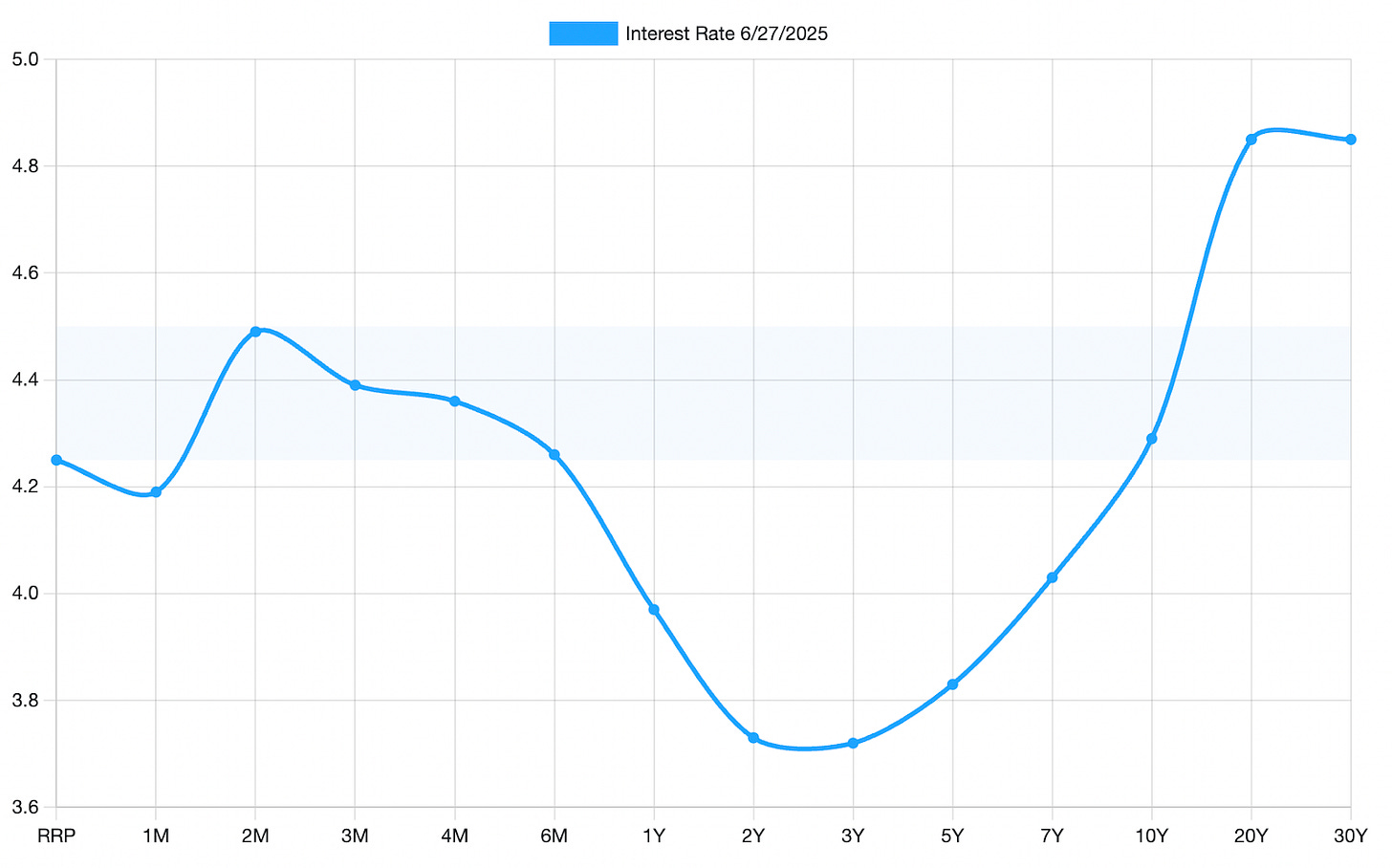

In theory, holding Treasuries boosts NIM. However, today's inverted yield curve complicates that logic:

This inversion flips the traditional logic:

Limited profitability: Long-term Treasuries yield less than short-term bills.

Interest rate risk: If yields rise, long bond prices plummet.

Liquidity risk: Long bonds are harder to sell quickly without severe losses, as Silicon Valley Bank painfully discovered.

Capital constraints (SLR): Long bonds consume more balance-sheet space compared to the income they generate.

When banks hold too many long-dated bonds under these conditions, their NIM suffers, which was central to Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse.

Yet despite this, the Treasury still needs banks to buy long-duration debt.

This is where relaxing the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) becomes crucial.

Lowering the SLR doesn’t increase bond yields, but it does reduce the capital cost of holding Treasuries. This is especially important for long-duration bonds, because:

Current rules heavily penalize long bonds due to their size and duration.

Relaxing rules frees up balance-sheet capacity, making longer bonds more economically viable.

If yields eventually decline, long bonds can appreciate significantly, offering banks capital gains not available with short-term bills.

Thus, even if short-term bills yield more now, a lower SLR makes holding duration attractive by aligning regulatory conditions with Treasury funding needs, without immediately hurting banks’ NIM.

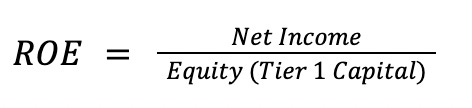

However, banks measure success not just by NIM, but ultimately by Return on Equity (ROE).

ROE: The Real Scoreboard

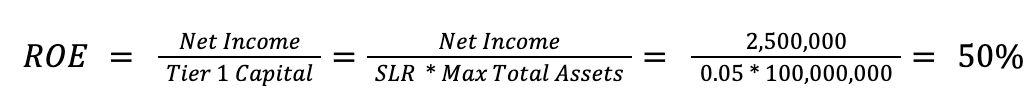

Return on Equity (ROE) measures how much profit a bank generates for each dollar of shareholder capital.

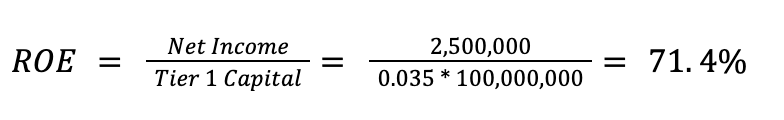

ROE is defined as

A higher ROE means more efficient profits → higher stock prices → larger executive bonuses.

A lower ROE signals underperformance—and shrinks compensation.

Here’s the constraint:

Raising new capital (by issuing shares) increases the denominator

Unless profits rise just as fast, ROE falls

That’s why banks hate issuing new equity: it dilutes shareholders and drags down returns

As a result, banks face constant pressure to extract more profit from the equity they already have. Maximizing ROE becomes a core strategic goal, not just for shareholders, but for executives themselves.

So banks are constantly playing the same game:

Maximize income. Minimize capital. Extract the highest return possible.

In a system built on leverage and spread, success isn’t just about how much a bank earns, it's about how efficiently it earns it.

Why Lowering the SLR is the Spark That Releases Systemic Pressure

This is where the SLR rollback becomes a game-changer.

A lower SLR expands balance-sheet capacity without requiring new equity. Banks can hold more assets, including long-dated Treasuries, using the same capital base. If those assets generate reliable spread income or appreciate when yields fall, ROE rises, without a single share being issued.

In short:

The SLR rollback removes the one constraint keeping banks from embracing duration risk.

Balance Sheet Impact

Lowering the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) from 5% to 3.5% unlocks significant balance-sheet capacity.

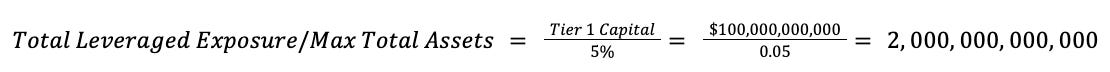

At a 5% SLR, $100 billion of capital supports up to $2 trillion in total assets:

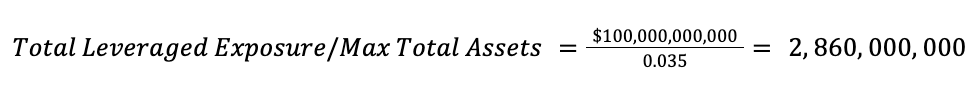

At a 3.5% SLR, the same $100 billion supports up to $2.86 trillion in assets:

That’s an extra $860 billion in lending or asset capacity.

Suddenly, long-dated Treasuries, previously penalized, become viable. The math flips:

Lowering the capital constraint changes the math for banks:

Before: “Avoid duration”

After: “Absorb duration”

Not because long bonds yield more, but because the regulatory cost has been cut.

And the impact is clearest on Return on Equity (ROE).

Let’s illustrate with a simple scenario:

How SLR Affects ROE (A Simple Example)

Assume:

$100 million in customer deposits at 2.0% interest

Invested in 10-year Treasuries yielding 4.5%

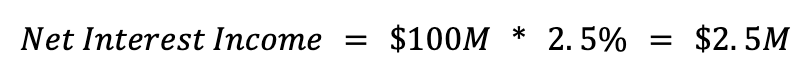

This generates a Net Interest Margin (NIM) of 2.5%, or a net interest income of $2.5 million.

Under a 5% SLR:

Under a 3.5% SLR:

Simply lowering the SLR boosts ROE by approximately 43% without issuing any additional equity.

The incentive loop is now complete for the banks.

If you’re a bank CFO or risk manager, the message is clear:

The system is now paying you more to take more duration risk.

More profit per dollar of equity. Higher stock prices. Bigger executive bonuses.

And that’s why lowering the SLR isn’t just a technical tweak.

It’s the match dropped into a room full of vapor.

Policy Context: Who's Holding the Lighter?

Banks don’t act in a vacuum.

Their actions follow signals from above. Regulatory structure is downstream from macro policy.

So yes, the SLR rollback is the spark.

But the one holding the lighter is the Fed.

The real question isn’t what banks will do.

It’s why policymakers lit the fuse in the first place.

Fed’s Urgent Dilemma

The Fed and Treasury urgently need buyers for long-term U.S. debt without restarting QE or depending on declining foreign support. As detailed in Post 1: Cracking the World Order, the U.S. faces three structural headwinds:

$9 trillion refinancing wall (2024–2027): Massive simultaneous debt maturities.

Shrinking foreign demand: Japan repatriating funds; China diversifying actively.

QE’s political toxicity: Fed asset purchases viewed as a controversial last resort.

At first glance, the solution might seem simple: just cut rates.

But that logic misunderstands how the yield curve works.

Rate Cuts Don’t Solve Long-End Pressure

Cutting rates primarily affects short-term yields (e.g., overnight loans, T-bills). However, long-term yields (10-, 20-, 30-year Treasuries) respond differently, shaped largely by:

Inflation and growth expectations

Duration risk (long-term uncertainty)

Treasury market supply-demand balance

For instance, investors expecting higher inflation typically avoid long-term bonds, reallocating capital into equities, commodities, or TIPS, driving long-term yields higher. This scenario unfolded precisely in September 2024: the Fed cut short-term rates, but long-end yields rose, a clear market rejection of the Fed’s optimistic recovery narrative.

Why Long-End Yields Matter So Much:

Persistently high yields intensify government debt burdens, tightening fiscal space and elevating borrowing costs economy-wide. Long-term Treasury yields directly shape:

Mortgages

Auto loans

Student loans

Corporate debt

For banks, U.S. Treasuries are considered risk-free. So if 10-year notes yield 4.25 - 4.50%, lending to anyone else must pay more, not just for credit risk, but for duration risk too.

So if long-end yields stay high, everyone pays more to borrow.

The economy slows.

Private credit dries up.

Risk assets choke.

That’s why lowering the SLR isn’t just a regulatory tweak. It’s an under-the-radar shift in credit architecture, one designed to:

push long-end yields lower

relieve balance sheet pressure

re-anchor the Treasury market without triggering the political blowback of QE

Igniting the Next Bull Cycle

But here’s the part no one’s pricing in: Despite the doom loops, towering debt walls, and policy paralysis, once the spark is lit, once the SLR is lowered, we’re about to ignite the most dramatic bull cycle in history.

Not because economic fundamentals look promising.

But because the plumbing has been rewired to force capital into risk.

If lowering the SLR succeeds in pulling bank capital into long-dated Treasuries, it does more than re-anchor yields. It systemically softens credit conditions:

Mortgage rates fall.

Business credit eases.

Asset prices rise.

And with Trump-era tax treatments like TIPS adjustments returning, real wages could tick higher.

Yes, inflation is a risk, but that’s not what this post is about.

This is about liquidity. And the setup is turning decisively bullish.

How the Liquidity Dominoes Fall

1. Looser capital rules give banks room to grow.

Cutting the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) means big banks can add more assets without raising fresh equity.

2. Banks pour the extra balance-sheet space into long-term Treasuries, driving those yields down.

With more balance-sheet space, banks can absorb duration. Demand for long-dated Treasuries rises. Yields fall.

3. Low bond yields mean lower real returns

When bond yields fall if inflation stays steady around 3–4%, the "real return", what investors earn after inflation, gets squeezed, sometimes approaching zero.

4. Investors seek higher returns by choosing riskier assets

Pension funds, insurers, and endowments need higher annual returns (6–8%). Because bonds aren't earning enough, these large investors shift into riskier assets like corporate bonds, stocks, private equity, real estate, and sometimes crypto.

5. Risk asset prices rise as capital flows accelerate

As investors move their money out of low-yielding bonds and into these riskier markets, they push prices up even if economic growth is moderate.

6. Stablecoins turn short-term Treasuries into high-speed digital dollars.

Backed 1:1 by dollars or short-term U.S. Treasuries (≤3-month T-bills), stablecoins are now legally recognized and rapidly moving mainstream. Unlike traditional payments, they settle instantly, 24/7, across crypto and fintech rails. This “always-on” liquidity allows capital to circulate through markets faster than ever, accelerating trading, lending, and capital flow, especially within digital asset ecosystems.

7. Increased liquidity drives asset prices higher

With more money flowing quickly into markets, asset prices tend to rise, assuming overall economic conditions remain stable.

Why it matters:

Easing the SLR isn’t just a technical adjustment—it’s the first domino in a systemic cascade:

Banks absorb duration → yields fall → real returns collapse → investors chase risk → stablecoins supercharge liquidity → markets melt up.

Inflation watch:

But more liquidity also increases the risk of price pressures. If inflation flares up again, the Fed may be forced to tighten faster, cutting the bull cycle short.

Shadow QE: Weaponizing the Dollar and Digital Rails:

That's how a few quiet policy tweaks ignite a bull cycle, without a press conference or the label “QE.”

As detailed in Posts 1–3 (Cracking the World Order, The Cold Room, Shadows Beneath the Ice), Washington isn't just fighting a debt crisis, it's strategically weaponizing the dollar to reshape global finance. At the heart of this strategy is stablecoin legislation, creating a modern digital version of the Cold War-era eurodollar system.

The Crypto Eurodollar Loop ->The Crime Supercycle

Today’s offshore dollar system isn’t built on European banks and wire transfers. It’s built on Tron and Ethereum, running at internet speed.

Here’s how the loop will work:

1. Tron clears the trade.

Since the Russia–Ukraine war, amid escalating sanctions and tighter capital controls, TRC-20 USDT (Tether on Tron) has become the dominant offshore dollar rail. Its advantages: near-zero fees, instant settlement, and easy mobile access. Tron now processes roughly half of all circulating USDT (~$80B).

2. Ethereum captures the float.

Cross-border businesses, OTC desks, and remittance providers don't just transfer digital dollars. They hold large idle balances between transactions. These balances will migrate from Tron to Ethereum or Layer-2 platforms, where they earn yields (around 3–6%) through DeFi protocols like Aave and Compound. Ethereum provides the deep liquidity and trusted DeFi infrastructure these users need.

History is repeating, faster and harder to track

Like the original eurodollar system during the Cold War, where Soviet-linked actors parked dollars in European banks to avoid U.S. asset freezes, the crypto eurodollar loop moves dollar liabilities outside the formal banking system. But now it's dramatically faster, larger, and harder to trace.

In short:

Tron High-velocity cross border payments infrastructure.

Ethereum: Offshore balance sheet, with Defi applications converting idle capital into yield.

Ironically, laws like the GENIUS Act intended to legitimize stablecoins inadvertently help shadow economies flourish. Once stablecoins are federally recognized, sanctioned entities, drug traffickers, and financial launderers gain seamless access to legitimate financial rails. The boundary between legal and illicit funds blurs, compliance barriers weaken, and regulators lose oversight.

This convergence doesn't just mirror historical parallel finance. It supercharges it. Illicit financial activity expands at the same speed and scale as the regulated market intended to control it, fueling what can only be described as a Crime Supercycle.

But here’s the twist: this shadow liquidity doesn’t stay in the shadows.

It feeds back into mainstream markets, blurring the line between black-market capital and sanctioned capital flows.

Now layer in:

A lowered SLR (more bank balance-sheet firepower)

Looming Fed rate cuts (cheaper capital)

Exploding stablecoin circulation (instant liquidity)

You don’t just get a market rally. You trigger the most exaggerated bull cycle in history, driven not by economic fundamentals but by rewired financial plumbing.

Banks Aren’t Just Buying Bonds. They’re Turning Them Into Digital Dollars

As previously discussed in Post 3, new legislation such as the GENIUS Act and STABLES Act would allow regulated institutions, not just banks, to issue stablecoins.

Here’s how the mechanism works:

Institutions acquire short-term U.S. Treasury bills (typically ≤ 93 days) and hold them in custody. In return, they issue digital tokens, stablecoins, fully backed by these T-bills. These tokens circulate freely as cash-equivalents, moving instantly across crypto and fintech rails.

Meanwhile, banks absorb long-duration Treasuries elsewhere on their balance sheets, especially as SLR constraints ease. This division of roles creates a two-part system:

Short T-bills → support stablecoin issuance and instant transactional liquidity.

Long bonds → fulfill the Treasury’s deep-duration funding needs.

At first glance, this may seem unrelated to central bank action. But functionally, it mirrors the effects of Quantitative Easing (QE):

Long-end Treasury demand rises (yields fall).

Digital dollars proliferate (liquidity expands).

The difference? This is QE without a central bank. No reserves are printed, and no assets sit on the Fed’s balance sheet. Instead, private institutions inject synthetic liquidity into markets, backed by real Treasuries, but circulating far faster and further than traditional deposits.

The risk? If confidence falters, and stablecoin holders rush to redeem, issuers must sell those T-bills, sparking forced liquidations that could disrupt both digital markets and bond pricing.

That’s why this setup isn’t just innovative, it’s shadow QE: all the liquidity, none of the central oversight.

Why this matters:

Synthetic liquidity feels safe, until something shakes confidence. If there's a crisis (e.g., rapid interest-rate hikes, falling bond values, or loss of trust), token-holders will rush to convert stablecoins back into real dollars.

To meet these sudden redemptions, institutions must quickly sell Treasury bonds, often at substantial losses. If too many redemptions happen simultaneously, the chain reaction is rapid:

Forced selling of bonds

Bond prices collapse

Panic spreads through markets

Liquidity dries up everywhere

In other words, the system is quietly leveraging its safest assets (Treasuries) twice: first as stable bank holdings, and again as freely traded tokens. While this appears innovative, it significantly increases systemic risk during periods of stress.

Put simply: converting Treasuries into digital dollars creates shadow QE, injecting liquidity without traditional safeguards. Under calm conditions, the system feels stable. Under stress, it's explosive.

That's where the story bends—and the fuse is already lit.

Markets are primed for a historic bull run, driven not by economic fundamentals, but by quietly rewired financial plumbing forcing capital into riskier assets.

Yet beneath the surface, another force gathers momentum. Every dollar that moves through stablecoin channels doesn't just chase yield. It bypasses controls, slips past compliance, and disappears into the shadows.

IV. Epilogue: Following the Flow

We've cracked the eggs, chilled the room, and watched shadows emerge.

Now the match is struck. Capital is set to surge through every channel Washington just widened. But these same rails will simultaneously carry unprecedented volumes of untraceable, extralegal dollars.

This sets up two parallel stories for 2025–26:

The Everything-Bubble: A once-in-a-generation melt-up as banks lever duration, liquidity gushes across markets, and sidelined cash chases yield.

The Crime Supercycle: The fastest-growing shadow economy in history, leveraging the very infrastructure intended to modernize finance.

Most analysts will chase the first story, because bubbles generate better headlines.

This Substack exists to map the second.

The next few posts will dive deeper on case studies in time and technical implementation of the soon-to-be open-sourced algorithm.

For anyone that wants to help me map it, please reach out!